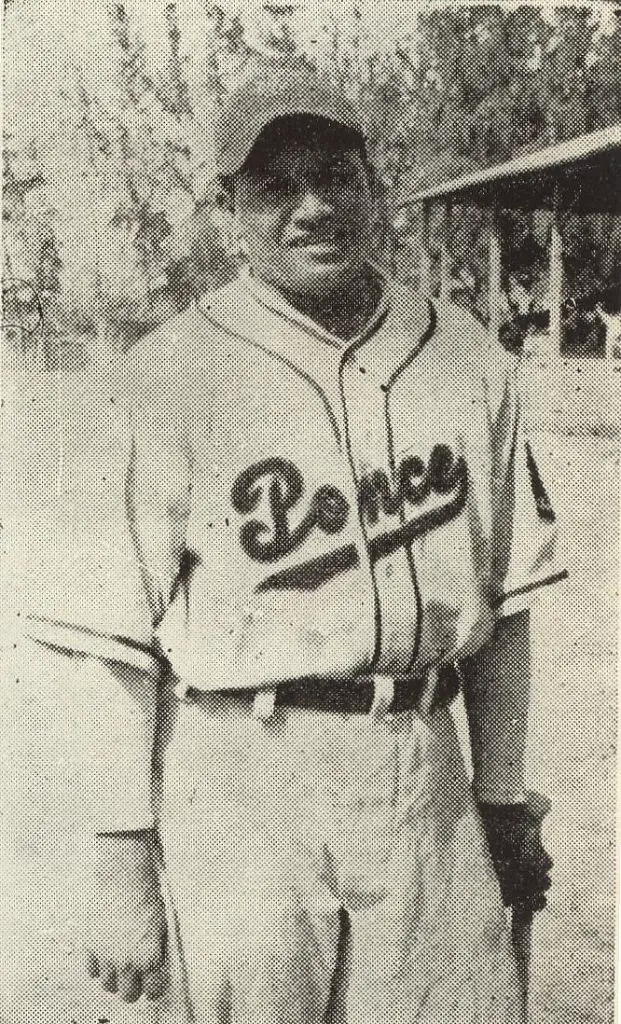

Pancho Coimbre

In the 1980s, I, like every other Puerto Rican boy, fell in love with baseball. My father had made sure that, although he gave us all freedom of choice in all things, when it came to sports, baseball was king. I grew up in the southern town of Ponce, a place that has a history of its own. Part of that town’s history is its legendary winter baseball team, the Leones de Ponce. One of the first teams to be assembled on the island at the beginning of the 20th century, part of my childhood was spent at Estadio Paquito Montaner cheering for young phenoms like Juan Gonzalez, Roberto Alomar, and Jim Thome as they tried to find their game. Sundays after church, it was to Montaner for a double header, on an island so small that the double header for your team would feature two different opponents in one day. All for the free price of admission for a child. It was a baseball utopia.

I was one of thousands of children playing in the Little Leagues in Ponce. I played for Valle Alto in Ponce. Our team was always good, often playing against teams from other towns on the island for Regional Championships. In 1988, after our coach’s pitching season was over, my father, as the perfectionist he was, thought that I needed more work on my swing. In a world without computers, iPads, and cell phones, what else would a six-year-old kid have to do but work on his swing? My father took me to a place called the Charles H. Terry Complex, a place that holds the distinction of being the oldest sports complex in use in Puerto Rico to this day and the second oldest in the Caribbean. This is also the place where, in 1899, the very first baseball game was played in Ponce.

In that complex, the city of Ponce had arranged for the children of the city to get some baseball coaching clinics. Every Saturday, children from all over town, whether it was baseball season or not (like there is a baseball off season in PR), would fill the Terry complex (colloquially known in Ponce as “El H. Terry”) and play baseball, but more importantly, they would be coached to strengthen their skills. This was not a team, as every child would show up with a different uniform on, which at the age of six bothered me, foreshadowing what would become an adult compulsion.

When I met my group of coaches, my six-year-old mind did not recognize who they were. The first observation I made was one that I am sure every child would make: they were much older than my Little League coaches. The adults present would point at them, and some would take pictures. Those who took their grandchildren to the clinics, many of whom were contemporaries with my father, recognized the coaches. The coaches would gather everyone around, and they would divide the children by ages and by coaches, rotating coaches as the clinics went on every week so that every child could get a chance at a different coach.

My father told me the coach who took me was a gentleman by the name of Pancho Coimbre. He was not in uniform that day; as I recall, he was wearing a pair of slacks and a guayabera and was walking with a cane. He had another gentleman helping him by the name of Juan Guilbe. I later made my way to the group of another coach, whose name was Millito Navarro. These two gentlemen were in full baseball uniform in their late 70s on a Saturday, ready to coach children young enough to call them “abuelo”. There were others, but these three gentlemen stuck in my mind because they were the most outspoken and with whom I had the most experience.

My six-year-old mind could not comprehend that I was being coached by former Puerto Rico Winter League players who also played in the Negro Leagues and later received the distinction of being cataloged as Major Leaguers, as the Negro Leagues were rightfully awarded that distinction in 2021. These gentlemen were unable to play in the National or American Leagues during their time because the same “courtesy” of segregation that was extended to African American players in both Major Leagues at the time was also extended to Afro Latino players. So, despite Puerto Rico having had a player born there make his MLB debut on April 15, 1942, by the name of Hiram Bithorn coincidentally five years before the day Jackie Robinson debuted, other Puerto Ricans could not play in the American or National leagues because of their African heritage.

Emilio Navarro

When the Negro Leagues got recognized as Major Leagues, that made my coaches, Navarro, Guilbe, and Coimbre the second, fifth, and seventh Puerto Ricans, respectively, to ever make the Major Leagues. Officially, Guilbe is credited with two seasons in the Negro Leagues in 1940 and 1947, playing for two teams, the New York Cubans in 1940 and the Cincinnati – Indianapolis Clowns in 1947. He had an ERA of 3.65 and 14 strikeouts in 24.1 innings pitched. He could also handle the bat well for a pitcher, collecting seven hits in 23 at-bats for a career batting average of .304.

Navarro played for the Cuban Stars East team of the Eastern Colored League in 1928 and the American Negro League in 1929. He is officially credited for 192 plate appearances, during which the middle infielder compiled .286 batting average, collecting 53 hits in 185 at-bats. Although he is chronologically the second Puerto Rican to play in the Major Leagues, he was the first to find consistent playing time in the Negro Leagues. By the time the Puerto Rican Winter League was officially organized, Navarro, 33, had played for Leones de Ponce and, in five seasons, was credited with 662 at-bats, 182 hits for a .272 batting average, and 39 doubles. Navarro would also go on to work with Leones de Ponce as a manager and administrator in the decades after. He was inducted into the Puerto Rico Sports Hall of Fame in 1953 and the Puerto Rico Baseball Hall of Fame in 1992.

Coimbre may very well be the best player you have never heard of. A player about whom the great Satchel Paige said, “could not be pitched to” and “nobody gave me more trouble ”. That is quite the complement to Coimbre, considering Paige pitched to Josh Gibson and Ted Williams, among others. Coimbre’s official Negro League numbers credit him with a .334 batting average, collecting 177 hits in 530 at-bats. He also had six Home Runs and 93 runs batted in. His OPS+ of 129 positioned him among the best offensive players during his career. Equally impressive is the fact that these official numbers that position Coimbre as one of the best players in the Negro Leagues from 1940 to 1944 are numbers Coimbre produced during his ages 31 to 35 seasons, when a baseball player’s production has slowed down. One can only imagine what his prime numbers were. Some sources credit Coimbre with a .377 batting average in the Negro Leagues, which would be the fifth-best of all time. His career in the Puerto Rico Winter League was just as impressive, having produced a batting average of .337 with 646 hits in 1,920 at-bats, 135 doubles, 17 triples and 24 Home runs. Perhaps the most impressive feat of Coimbre is that he would never strike out. No, that is not a figure of speech. Coimbre spent three consecutive seasons in Puerto Rico from 1939 to 1942, in which he did not strike out. Again, not a figure of speech. He did not record a strikeout in 550 at-bats during those three seasons. Although he was not known as a Home Run hitter, he still had more Home Runs (24) than strikeouts (20) in 1.920 at-bats in the Puerto Rico Winter League. One final thought about Coimbre. In what could be considered “baseball heresy” in Puerto Rico, one person once suggested Coimbre was a better player than Clemente. Put away your stones. The person who pronounced “heresy” was Clemente himself. Coimbre tragically died in a house fire in 1989, and the coaching clinics that bore his name would fold not long after. Guilbe passed away in 1994. Navarro did so in 2011, having been the oldest and last surviving member of the American Negro League. I grew up hearing my oldest brother and his generation brag about having their dads take them to clinics offered by Clemente all over the island. Many Puerto Ricans to this day still have pictures in their homes and offices featuring them as children in these clinics posing with The Great One, much to my illogical envy. Clemente died more than a decade before I was born, so I just read about him. Having been raised in Puerto Rico, I could only dream about seeing the great Clemente up close. Little did I and thousands of other children in Ponce know that we were also coached by legends, and we had no idea.